The "Minor Arpeggio Trick"

Applying the Trick

I was recently introduced to a neat concept by a teacher at my university, known as the “minor arpeggio trick” (or “minor arpeggio secret” by the bassist Chris West). It can be summarized as following (from Wikipedia):

If we can maintain the same tension while plucking a string twice, 3 times, 4 times that length, etc. the undertone series will unfold downwards, containing the minor triad. Similarly, on a wind instrument, if the holes are equally spaced, each successive hole covered will produce the next note in the undertone series.

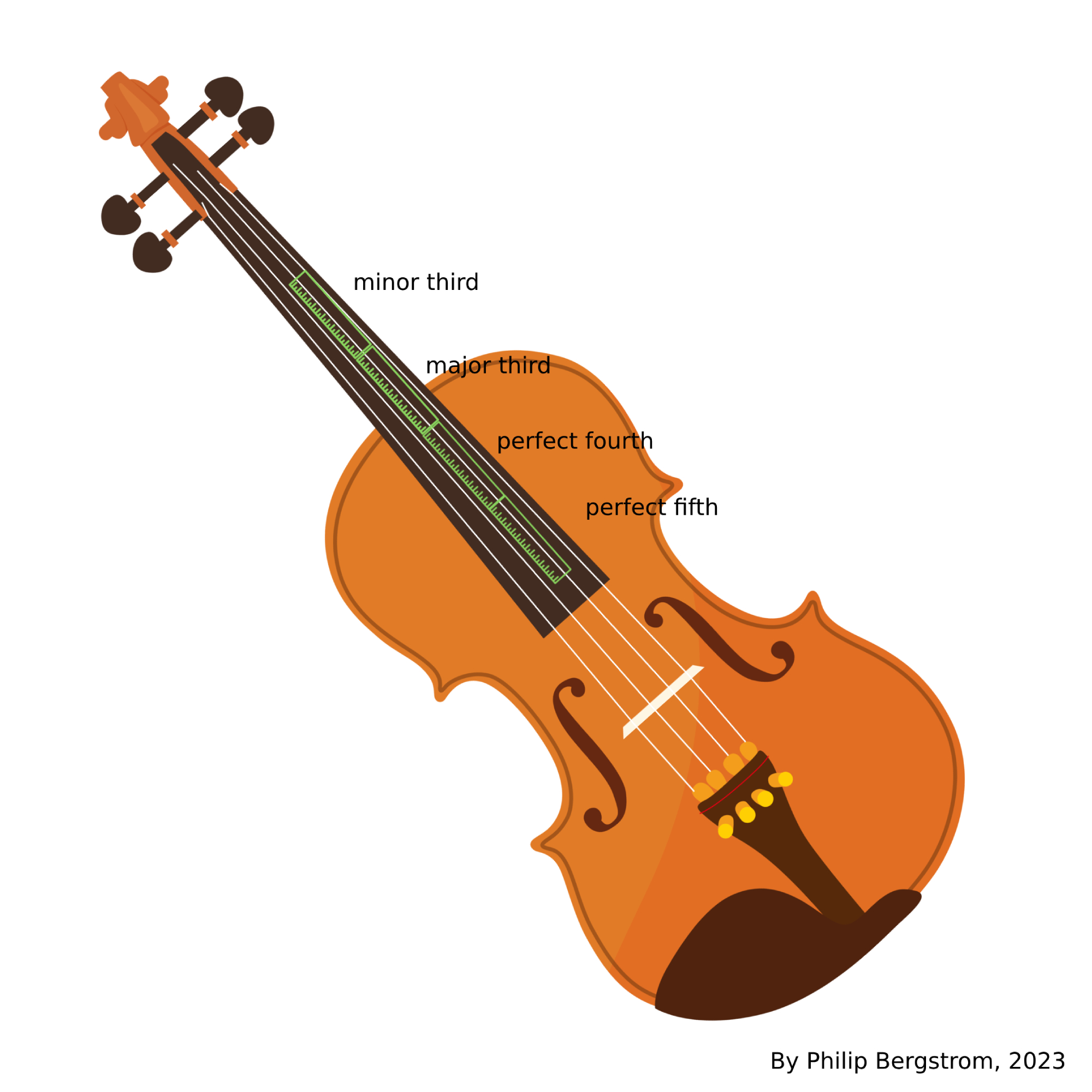

For string players, this means that the distances corresponding to the intervals of a perfect (justly intonated) minor arpeggio will be exactly equally spaced on the fingerboard, as illustrated in the figure below:

To illustrate the phenomenon in a context, assume you are playing a E with your first finger followed by a G with your third finger on the same string (a just minor third). If you shift up to the G with your first finger, your third finger will land on a B (a just major third) if you kept the distance between your first and third finger unchanged. Similarly, if you shift your first finger from the G to the B, your third finger will land on an E (a perfect fourth) an octave higher than your starting note. This is followed by a perfect fifth and an octave.

This “trick” will work regardless of your starting note or position, and becomes especially useful for double bassists since they often have to perform shifts with a constant hand frame. It could also be used to determine whether you need to increase or change the distance between your fingers when shifting up or down a string.

Why it works

When a string’s length is multiplied or divided by a whole number, the ratios between the old and new lengths will also be a whole number, giving rise to just intervals, or pure intervals. For example, if we imagine a string producing the fundamental tone F that is 6 units long and divide it into 6 equally long parts, the following intervals would arise:

| Length ratio | Interval | Pitch |

|---|---|---|

| 1:6 | 6:1 | C6 |

| 2:6 | 3:1 | C5 |

| 3:6 | 2:1 | F4 |

| 4:6 | 3:2 | C4 |

| 5:6 | 6:5 | Ab3 |

| 6:6 | 1:1 | F3 |

In other words, the tones produced by the shortened strings with equal lengths form a pure F-minor arpeggio, explaining the “trick” above.

A more systematic way of determining what pitches lengthening or shortening a string equidistantly produces, is to consider the undertone series. While the overtone series consists of tones with wavelengths that are whole number divisions of a fundamental wavelength, the undertone series consists of the opposite, i.e. wavelengths that are whole number multiples of a wavelength. Consequently, when we imagine a string shortened by equal distances such as in the table above, the fundamental of each new string will be found in the undertone series.

As an example, the 1-6th tones of the undertone series on C form the shape of the pure minor arpeggio from F that we saw above:

Thus, we could theoretically apply “the minor arpeggio trick” for any consecutive intervals found in the undertone series. However, from the 7th undertone and onwards, the pitches in the series start to diverge substantially from the pitches used in equal temperament, making them more difficult to use in a practical context.

If you want to further explore how to apply these concepts on the double bass, check out the book Fractal Fingering by bassist David Allen Moore.